India

With deeply rooted religious cultural features, India is one of the most religiously diverse nations in the world. In India, religions have always been playing a central and definitive role in the life of the country and most of its people. As one of them, Buddhism was originated in India 2500 years ago and is still practiced today.

With deeply rooted religious cultural features, India is one of the most religiously diverse nations in the world. In India, religions have always been playing a central and definitive role in the life of the country and most of its people. As one of them, Buddhism was originated in India 2500 years ago and is still practiced today.

Buddhism was founded by Siddharta Gautama, a prince of Shakya clan, at the beginning of the Magadha period (546-324 BC), in the plain of Lumbini, today’s southern Nepal. To search the real truth of life and world, prince Gautama abandoned his luxurious royal life when he was 29 years old and started to live as an ascetic and later “in the middle way”. At 35, he founded Buddhism. He was venerated by his disciples and Buddhists as “Gautama Buddha” or simply “The Buddha” meaning the enlightened one, or “Sakyamuni” which literally means “the sage of the Shakya clan”. During his following 45 years disseminating Buddhism, Shakyamuni traveled mainly in the Gangetic Plain area of central India, teaching his doctrine and discipline to an extremely diverse range of people, leaving legends behind his life.

The evolution of Buddhism in India can be roughly divided into five periods so as to reach a better understanding of it.

The first period is early Buddhism, which covered about 3 to 4 centuries starting from Shakyamuni. This period was highlighted by initial foundation by Siddharta Gautama, rise of Sangha, affirmation of fundamental principles through several councils, royal acceptance of Buddhism and Buddhism’s spread beyond India.

In the 5th century BC, Gautama founded Buddhism, established initial Sangha and disciplines, and advocated fundamental doctrines. Buddhism worships no almighty, creative god, or even the Buddha himself, and encourages all Buddhists including monks and laities to discover the truth at his own discretion, guided by Dharma, of course. The Four Noble Truths constitutes basic tenets – existence is suffering, the cause of suffering is desire, the suffering can be put to cessation, and the way to cease suffering is the Noble Eightfold Path. And, by adherence to Three Jewels and Precepts (five, eight, ten or even more precepts depending on later different followers of different schools), through prajñā (wisdom), śīla (ethic conducts), and samādhi (mental discipline), people thus can cultivate themselves to attain the ultimate happiness of Nirvana, and cast off samsara.

There were several major councils in the early Buddhism period. The first Buddhist council was held soon after the death of the Buddha, at Rajagriha (today’s Rajgir of India), under the patronage of king Ajatasatru of the Magadha empire. It recorded the Buddha’s sayings (sutra) and codified monastic rules (vinaya): Ananda, cousin and main disciple of the Buddha, recited the discourses of the Buddha, and Upali, another disciple, recited the rules of the vinaya. Those later became the basis of the Pali Canon, which since then has been the orthodox text of reference throughout the history of Buddhism. The second Buddhist council was convened by King Kalasoka and held at Vaisali, mainly discussing matters about vinaya concerning bhikkus and bhikkunis. During this council, there began to show signs of early Buddhist schism though many scholars believe there was no actual split happening in Sangha.

The third council was sponsored by famous Ashoka, the Mauryan Emperor, in 250 BC. This council was also held to reconcile the early different schools and purify Buddhist movements. The Pali Canon received formal recognition at this time. Ashoka, who renounced violence and proselytized to Buddhism, contributed greatly to early Buddhism’s dissemination by merging political state with Buddhism. Under his patronage, Buddhism had its first large scale of spread beyond India. Among nine missionary groups sent by Ashoka, Mahinda, son of Ashoka, went to Sri Lanka, officially introduced Buddhism, and proselytized the king over there. Ashoka promulgated series of edicts to promote Buddhism, built thousands of stupas and viharas, and made himself probably the most important patronage and king in the history of Buddhism.

The second is the “sectarian” period of Buddhism, lasting from about the 1st century BC to the 3rd century AD. This period is marked by sprout and formation along lines of Sthaviravāda and Mahāsaṃghika. Each major school has several sub-divisions, eighteen or twenty according to different sources , brewing thoughts and theories for later Mahayana and Hinayana.Around 100 BC, Kushan emperor Kanishka convened the fourth council at Jalandhar or in Kashmir. This council is usually considered the formal rise of Mahayana Buddhism and its secession from Theravada Buddhism, though Theravada Buddhism did not recognize it and even called it heretical. Another fourth council was held by Theravada monks in Sri Lanka, in opposition of Kashmir monks’ standings.

The third century saw the advent of perhaps the most influential Buddhist thinker after the Buddha, Nagarjuna. His writings became basis of the Madhyamaka (Middle Way) school, which was transmitted to China under the name of the Three Treatise (Sanlun) School. Born into a Brahmin family, Nagarjuna used Sanskrit in writing down most of his works. Nāgārjuna’s primary contribution to Buddhist philosophy is in the development of the concept of śūnyatā, or “emptiness,” which brings together other key Buddhist doctrines, particularly anatta (no-self) and pratītyasamutpāda (dependent origination). Nāgārjuna was also instrumental in the development of the two-truths doctrine, which claims that there are two levels of truth in Buddhist teaching, one directly (ultimately) true, and one conventionally or instrumentally true. Those thoughts also contributed to the theoretical basis of Mahayana.

The third period is the Gold Age (about 4th-6th century AD) for Buddhism not only in India, but also in other areas. By 538 AD, Mahayana had been flourished and spread in the East from India to South-East Asia, and towards the north to Central Asia, China, Korea, and finally to Japan. In the meantime, Theravada also had some new developments. Abhidharma were used to re-interpret the narrative sutra tradition and generate a systematic category of Buddhist scriptures, generalizing and re-organizing the doctrines piecemeal presented in previous scriptures and discourses.

Besides geographical extension, another obvious feature about Buddhism during this period is that numerous Buddhist thinkers and philosophers emerged, producing varieties of new points of view. Buddhism began to transfer from mainly disseminatings Buddha’s teachings and discourse to also including new theories about worldly phenomena. To name a few most prominent scholars during this era, Nagarjuna and his disciple Aryadeva, Buddhaghosa, Asanga and his brother Vasubandhu, and Dignaga, etc. The emergence of those scholars and their theories greatly enhanced the philosophical system of Buddhism and also boded a future trend of scholasticism in Buddhism. After hundreds of years’ patronage from Kings, royal families, and rich merchants, there had already been some kind of vihara economy, which could support monks living in monastic centers instead of solicitation for en route food and clothing offers in the early years of Buddhism. As the power of the Gupta Dynasty was at its peak, society could surely provide more for monks’ preaching and research practices. Dating its foundation back to the 5th century AD according to archeological excavations, Nalanda is the most famous one among those monastic centers, and it gradually became the largest and most influential Buddhist university in history.

The accomplishments were achieved so remarkably that many enthusiasts came to India as pilgrims. Fa Xian, a Chinese monk, came to India via land in 402 and returned from Sri Lanka by sea in 412. His Record of Buddhist Kingdoms contains extremely valuable information about Indian Buddhism at that time.

The fourth period of Indian Buddhism – decline, lasted more than a thousand years. After the 6th century, Buddhism gradually lost the enthusiastic royal and social support, and the world Buddhism center transferred out of India. Buddhism underwent a long time of decline in following centuries. The milestone of Indian Buddhism’s decline is the 1193 destruction of Nalanda by Khilji’s Islamic forces. The exact reason for Buddhism’s decline in India is still under research and dispute. The following factors, however, contributes to it: The invasion of Islamic countries and dissemination of Islam in India. The new rulers destroyed temples, burned Buddhist libraries, drove away or even killed monks. The revival of Hinduism. Hinduism was originated in India, existed for a very long time, and had some common features with Buddhism, whose decline also gave Hinduism new proselytes. The trend of scholasticism and “tantra-ization”. Those contributed to Buddhism’s prosperity as well as diminished its attraction for common people – abstruse in one direction and mysterious in another. As recorded by the Chinese monk Xuanzang in his Journey to the West in the Great Tang Dynasty, before the end of the 7th century, he already saw some deserted Buddhist temples in central Asia. At the same time, Buddhism had also been in relative decline in Northern India. The extrinsic powers pressing down Buddhism had not reached and worked far enough. After the 13th century, Buddhism almost disappeared in India after more than one thousand years of prosperity, leaving only some continuous practices in Himalayan areas such as Ladakh, Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim, etc, where Tibetan culture was influential.

At the beginning of the 20th century, however, there emerged a movement of Buddhism revival in India. Historical research and increased contact with the rest of the Buddhist world led to renewed interest in Buddhism. Thinkers such as Iyothee Thass, Brahmananda Reddy, and Dharmananda Kosambi began to discuss it in very favorable terms. During the 1930s, Ambedkar, who declared in 1935 his intention to leave Hinduism because he believed it perpetuated caste injustices, became interested in Buddhism as an alternative. After publishing a series of books and articles arguing that Buddhism was the only way for the Untouchables to gain equality, Ambedkar publicly converted on October 14, 1956 in Nagpur. He took the three refuges and five precepts from a Buddhist monk in the traditional manner and then in his turn administered them to the 380,000 of his followers that were present. Subsequent mass conversions on a lesser scale have occurred since then. Three-quarters of these Indian Buddhists live in Maharashtra. Buddhists form majority population in the Indian states of Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh and Ladakh region of Jammu & Kashmir, and include a small number of tribal peoples in the region of Bengal and Tibetan refugees.

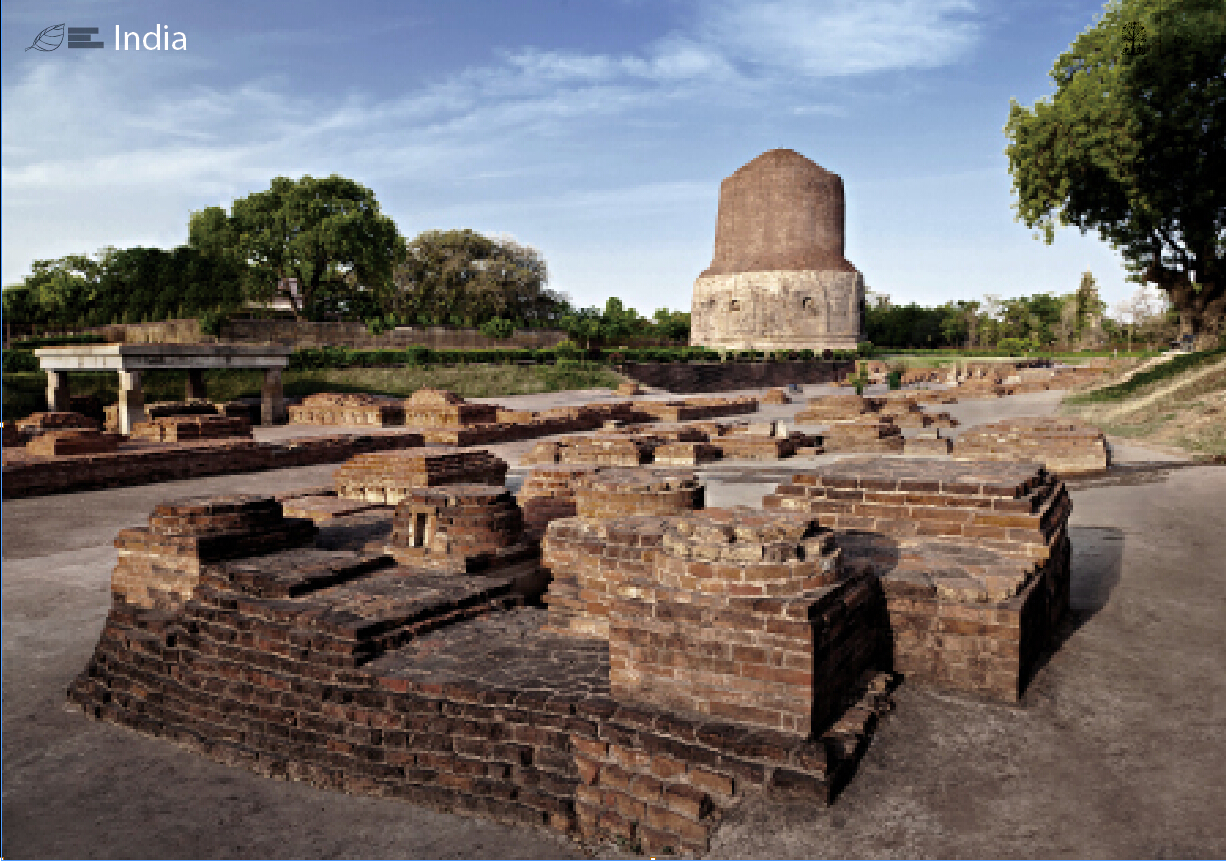

According to the latest census of 2001 in India, there were nearly eight million Buddhists, accounting for about 0.8 percent of Indian population.India is not a major Buddhist country in the world; it is indeed the most important place of pilgrimage for Buddhists. The origination of Buddhism and prosperity for more than a thousand years gives India great treasures in the history. The Buddha once told his disciples that a pious Buddhist should visit four places: where his was born, where he reached enlightenment, where he was first taught, and where he died. Today, expect Lumbini, the place where Buddha was born and located in Nepal near its border with India, the other three places are in India. Bohd Gaya, where he reached enlightenment, is located at a village in Bihar state in eastern central India. Sarnath, also meaning deer park (Mrigadawa) is the place where Buddha delivered his first preachment, located several miles north of Varanasi (Barnes). It also has an inscribed pillar by Emperor Ashoka and a famous stupa built in the 7th century. Kusinara, where the Buddha attained parinirvana, is a town in Uttar Pradesh state. There are also other famous Buddhist places connected to the life of Gautama Buddha such as Savatthi, Pataliputta, Gaya, Vesali, and Varanasi, etc. An archeological site in northern Bihar state, Nalanda had been the most important Buddhist monist center in the world for several centuries. Nalanda is often mentioned as a Buddhist university, housing thousands of monastic teachers and students at its peak in history. The noted Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang and Yijing provided vivid accounts of it in the 7th century. Nalanda continued its prosperity to the 12th century until it was destroyed by Muslim forces. Those places have been receiving many pilgrims from the world for a very long time.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka is an island country in the Indian Ocean, off the southeastern coast of South-Asia subcontinent. Today, of its people little more than 20 million, roughly 75% are Buddhists.

Sri Lanka is the oldest continually Buddhist country in the world. In the first half of the 3rd century BC, when Sri Lanka under the reign of king Devanampiya Tissa, Buddhism was officially introduced into this island by Mahinda, son of Ashoka the Great who was at that time the ruler of Maurya Empire in today’s eastern India. By that time, these two countries had already established a good relationship through exchange of ambassadors and valuable gifts between the kings. Ever since then, Buddhism has been held as Sri Lanka’s major religion, in most time as its actual national religion.Buddhism began as an intellectual and ethical movement in the 6th century BC in India. More than two hundred years later, when Indian missionaries brought Buddhism to Sri Lanka, they took not only teachings of Buddha but also the culture and civilization of the Indian continent. According to research, all rites, ceremonies, festivals and observance concerning Sri Lanka Buddhism at that time were only in slight difference and modification with Indian Buddhism. Pali was the language that Buddha used in his discourses, for instance, and perhaps it is the language closest to Sanskrit.

The fact that Sri Lanka is one of the few most important Buddhist countries in the world lies to not only its longest history of Buddhism, but also its unique contribution to Theravada Buddhism and its pivotal role in the dissemination of Buddhism. Nearly all of the early schools of Buddhism in the first five hundred years are extinct today, though majority of their fruits have been conceived and sprouted in today’s India and its peripheral areas. Theravada (historically known as “Sthaviravāda”), originated from India’s earlier Buddhism schools, was transmitted to Sri Lanka and later flourished into one of two major branches of Buddhism nowadays after centuries of vicissitude. The early Buddhist documentations of Sri Lanka were initially written in Sinhalese, the local language of Sri Lanka. Indian Buddhist commentator and scholar Buddhaghosa (literally “voice of Buddha” in Pali language) translated the original Sinhalese commentaries into Pali, which perhaps symbolizes the peak of the early Sri Lanka Buddhism. His Visuddhimagga (Pāli: Path of Purification) is a comprehensive manual of Theravada Buddhism that is still read and studied today. The book is divided into sections on Sīla (ethics), Samādhi (meditation), and Pañña (wisdom). Theravada contributed to and preserved the earliest systematical documentations of Buddha’s oral sayings and teachings, known as Tipitaka or the Pali Canon, which has remained as the only existing complete Nikaya (Hinayana) scriptures and been recognized by Buddhists all over the world. That is perhaps partly because that, it is said, Buddha himself explicitly forbade translation of his discourses into Sanskrit, an elitist religious language at that time. Thus, Theravada has never been switched to Sanskrit. It is interesting, though, Pali, as a language, gradually became a scholarly or elite language as well.

Besides India, Sri Lanka played a critical role in the ensuing process of Buddhism dissemination. It is the pivot through which Theravada spread to Southeast Asian countries in the Middle Ages, roughly between the 11th and 15th centuries. After the golden era between the 4th and 6th centuries in India, as the newly-emerged Mahayana came to dominate the period, Buddhism witnessed its several-century-long continuous decline. Except Tang Dynasty China and its surrounding areas, Buddhism suffered greatly in India and Central Asia under the dual impacts of Muslim invasion and Hinduism resurgence. As a result, not only South and Central Asian Buddhism was set back to so serious an extent that it almost extinguished, but Buddhism (primarily Mahayana) which had already spread to Southeast Asia declined as well. During that period of history, however, Theravada in Sri Lanka, apparently survived much less affected, gradually spread to Southeast Asia areas via trade route by sea. That is why today Theravada takes a dominant position in Buddhism of Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos.

Nevertheless, much earlier than that, as history reveals, Sri Lanka already spread Buddhism by this course. It is believed that Sanghamitta, who is believed the daughter of Emperor Asoka, came to Sri Lanka and started the first nun order in the 3rd century BC, though the order later died out around the middle of the 11th century AD. In 429 AD, on the request of China’s Han Dynasty emperor the nun from Anuradhapura was sent to China to establish the Nun Order, which was later spread to Korea. And Fa Xian, the famous 4th century Chinese monk, pilgrim and tourist, returned to his motherland by sea also, taking copies of scriptures with him. From a broader point of view, Sri Lanka remained a must-go place in the sea course of increasing trade between East/Southeast Asia and West Asia/Europe in the second millennium AD, not to mention the island itself as a place famous for its variety of gemstones and spices.

Along with the increasing sea trade, Sri Lanka was also subject to significant impacts, culturally and religiously. The proximity of Sri Lanka to India resulted in invasions and immigrations by Tamils and Hindus, and the Chola of South India also conquered Anuradhapura in the early 11th century. All those contributed to early Sri Lanka Buddhism’s suffering and decline after several centuries of prosperity. The Portuguese conquered the coastal areas in the early 16th century and introduced the Roman Catholic religion, followed by Dutch and British. As the British won control at the beginning of the 19th century Buddhism was well into decline, with English missionaries flooding the island. In the meantime, Theravada Buddhism also was spread to Asia, the West and even Africa.

A movement to revive Buddhism in Sri Lanka began in the second half of the 19th century through the efforts of monk Gunananda. Colonel Henry Steele Olcott, an ardent American abolitionist came to Sri Lanka in 1870s and enthusiastically supported the revival of Buddhism, followed with aid from a young Sri Lankan Dharmapala. Those movements created widespread support for Buddhism in Sri Lanka. Olcott and his society even managed to persuade the British governor to make Vesak, the chief Buddhist festival, a public holiday. By the mid-20th century, Buddhism was once again as strong as it had been on the island.

While Theravada is used to refer to a widespread school of Buddhism, “Sinhalese Buddhism” can be used to refer to local Sri Lanka Buddhism, which integrated various religious and cultural elements over its two thousand years of embracing Buddhism. In the modern era, Theravada Buddhism in Sri Lanka can be divided into three major sects:

Siyam Nikaya. In the 18th century, the official line of monastic ordination had been broken since monks at that time no longer knew the Pali tradition. The Kandyan king invited then the Theravada monks from Thailand to ordain Sinhalese novices; it was set up later as a reformed sect that enlivened study and proliferation of Theravada Buddhism in Sri Lanka.

Amarapura Nikaya. This sect was initiated by members of rising low-country castes discontent with monopoly over the monastic community by the upper castes in the 19th century. The sect was subsequently slit along the caste lines.

Ramanna Nikaya. This sect was established in the late 19th century as a result of disputes over some points of doctrine and the practice of meditation.

Each major sect also has various subdivisions, which maintains its own line of ordination. Caste usually determined membership in many of the sects. The members of the Buddhist monastic community preserve the doctrinal purity of early Buddhism, but the lay community accepts a large scope of other beliefs and religious rituals, many features of which came from Hinduism and very old traditions of gods and demons.

Taking advantage of the close relationship with South Asia subcontinent, either cultural or geographical, Sri Lanka is a place of legend and thus a place of pilgrimage. Soon after the advent of Buddhism in Sri Lanka, Sanghamittha, a Bhikkuni and daughter of Emperor Ashoka, brought a branch of Bodhi tree under which the Buddha had reached the enlightenment. According to legend, the tree that grew from this branch is near the ruins of the ancient city of Anuradhapura in the north of Sri Lanka. The tree is said to be the oldest living thing in the world and is an object of great veneration.

Legend also has it that Buddha himself visited Sri Lanka several times, three maybe. The Buddha’s visits were not confined to the Theravada tradition at that time, of course. The Lankavatara Sutra, the seminal text of the Ch’an and Zen schools of Buddhism, was believed to be the teachings of Buddha while he was in Sri Lanka, sitting on Sri Pada “which shone like a jewel lotus, immaculate and shining in splendor”. The Chrakasamvara Tantra even mentions Buddha flying to Lanka and leaving the impression of his foot on a mountain. Theravada Buddhism believes no creative god. Buddha, however, became a transcendent divine being with miraculous powers, even his relics.

The island’s many temples enshrine some of the most revered relics in the world, the most important being the Buddha’s tooth, a strand of his hair and his begging bowel. The sacred Tooth Relic (thought by many to be a substitute) that is venerated in the Temple of the Tooth in Kandy. The annual procession of Perahera held in honor of the sacred Tooth Relic has become a symbol of the island’s cultural tradition, an important event of the country, serving as a force of unity for the Sinhalese in following centuries.

By about the 3rd century AD a pilgrim’s circuit consisting of sixteen sacred places had been established, most of which were associated with Buddha’s legendary visits to the island. Of these sixteen places, seven are in Anuradhapura, a city once remaining to be the country’s capital for a long time, and the rest are spread widely throughout the country.

Because of its longest history of Buddhism, Sri Lanka owns many ancient Buddhist relics. Since its founding in 1890, Sri Lanka’s Archaeological Survey has discovered and excavated hundreds of ancient temples, monasteries, shrines and other monuments. At many of these sites inscriptions have been found recording the names of the places, gifts given to various institutions, how much they cost, the names and titles of the donors, what year in the reign of certain kings the gifts were made, and so on.

myanmar

Myanmar

Myanmar or Burma, officially Union of Myanmar is a country in Southeast Asia. It is bounded on the west by Bangladesh, India, and the Bay of Bengal, north and northeast by China, east by Laos and Thailand, and south by the Andaman Sea. Buddhism in Myanmar is predominantly of the Theravada intermingled with local beliefs, practiced by 89% of the ethnically diverse 45-million population, especially among the Bamar, Rakhine, Shan, Mon, and Chinese. The two major languages are Pali, the liturgical language of Theravada and English.

The culture of Myanmar is deemed synonymous with its Buddhism. There are many Burmese festivals all through the year, with most of them related to Buddhism. The Burmese New Year, Thingyan, also known as the water festival, has its origins in Hindu tradition but it is also a time when many Burmese boys celebrate shinbyu, a time when a Buddhist boy enters the monastery for a short time as a novice monk. It is the most important duty of all Burmese parents to make sure their sons are admitted to the Buddhist Sangha by shinbyu.The history of Buddhism in Myanmar extends nearly one thousand years. The Sasana Vamsa, written by Pinyasami in the 1800s, summarizes much of the history of Buddhism in Myanmar.

During the reign of King Anawrahta, Theravada Buddhism became prevalent among the Burmese. Prior to his rule existed a form of Mahayana Buddhism, known as Ari Buddhism. It included the worship of Bodhisatta and nagas, and corrupt monks. Anawrahta was converted by Shin Arahan, a monk from Thaton to Theravada Buddhism. In 1057, Anawrahta sent an army to conquer the Mon city of Thaton in order to obtain the Tipitaka Buddhist canon. Mon culture, from that point, came to be largely assimilated into Bamar culture in Bagan. Despite attempts at reform, certain features of Ari Buddhism and traditional nat worship continued. Following kings of Bagan built such a large number of monuments, temples, and pagodas in order to honor Buddhist beliefs and tenets that Bagan soon became a major archaeological site. Burmese rule at Bagan continued until the invasion of the Mongols in 1287.

The contact with Sri Lanka was very important for the growth of Buddhism in Pagan. It started with the friendship of Anawratha and Vijayabahu, both of whom fought for Buddhism: Anawratha to establish a new kingdom, Vijayabahu to maintain an old one from the Hindu invaders. They supported each other in struggles and together re-established the Theravada doctrine: Anawratha sending bhikkus to Sri Lanka to revive the Sangha, while Vijayabahu reciprocated by sending the sacred texts. The continued contact between the two countries was beneficial to both: many a reform movement, purifying the religion in one country spread to the other as well. Bhikkus visiting from one country were led to look at their own traditions critically and to reappraise their practice of the Dhamma as preserved in the Pali texts. After the fall of the main Buddhist centers in southern India, centers which had been the main allies of the Mon Theravadins in the south, Sri Lanka was the only ally in the struggle for the survival of the Theravada tradition.

During the Pagan period, there were some great scholars and writers. Aggavamsa completed his most famous Saddaniti in 1154, and he was also the teacher of King Narapatisithu (1167-1202). Others are Saddhammajotipala, Vimalabuddhi, etc. Their works contributed to development of Buddhism texts and Pali language.

Afterward, the Shan established themselves as rulers throughout the region now known as Myanmar. Thihathu, a Shan king, established rule in Bagan, by patronizing and building many monasteries and pagodas. Bhikkus continued to be influential, particularly in Burmese literature and politics.

The Mon kingdoms, often ruled by Shan chieftains, fostered Theravada Buddhism in the 1300s. Wareru, who became king of Mottama (a Mon city kingdom), patronized Buddhism, and established a code of law (Dhammathat) compiled by Buddhist monks. King Dhammazedi (1472-1492) takes a special place in history of Buddhism in Myanmar for his unifying Sangha in Mon country and purifying bhikku orders. Dhammazedi, formerly a Mon monk, established rule in the late 1400s at Innwa and unified the Sangha in Mon territories. He also standardized ordination of monks set out in the Kalyani Inscriptions. Dhammazedi moved the capital back to Hanthawaddy (Bago). His mother-in-law Queen Shin Sawbu of Pegu was also a great patron of Buddhism. She is credited for expanding and gilding the Shwedagon Pagoda giving her own weight in gold.

The Bamar, who had fled to Taungoo before the invading Shan, established a kingdom there under the reigns of Tabinshwehti and Bayinnaung who conquered and unified most of modern Myanmar. These monarchs also embraced Mon culture and patronized Theravada Buddhism.

In the reigns of succeeding kings, the Taungoo kingdom became increasingly volatile. In the mid-1700s, King Alaungpaya expanded the Bamar kingdoms and established the Konbaung dynasty. Under the rule of King Bodawpaya, a son of Alaungpaya, a unified sect of monks (Thudamma) was created within the kingdom. Bodawpaya restored ties with Sri Lanka started by Anawrahta, allowing for mutual influence in religious affairs. In the reigns of the Konbaung kings that followed, both secular and religious literary works were created. King Mindon Min moved his capital to Mandalay. After Lower Burma had been conquered by the British, Christianity began to gain acceptance. Many monks from Lower Burma had resettled in Mandalay, but by decree of Mindon Min, they returned to serve the Buddhist laypeople. However, schisms arose among the Sangha, which were resolved during the Fifth Buddhist Synod, held in Mandalay. From 1868-1871 in the Kuthodaw Pagoda, the Tipitaka was engraved on 729 marble slabs, which formed the basis of the revision work of the Three Pitakas done under the auspices of the Sixth Buddhist Council held in Rangoon during 1954-1956. A new hti (the gold umbrella that crowns a stupa) encrusted with jewels from the crown was also donated by Mindon Min for the Shwedagon in British Burma.

Sasanavamsa, a chronicle written in Pali by a bhikku for the Fifth Buddhist Council held in Mandalay in 1867, mentions several alleged major events, i.e. the Buddha’s several visits to Myanmar, and the arrival of his Hair Relic in Ukala (Yangon) soon after the Buddha’s enlightenment.

During the British administration of Lower and Upper Burma, government policies were secular, and monks were not protected by law. Likewise, Buddhism was not patronized by the colonial government. This resulted in tensions between the colonized Buddhists and their European rulers. There was much opposition to efforts by Christian missionaries to convert Burmese people (Bamar, Shan, and hill tribes). Today, Christianity is most commonly practiced by the Chin, Kachin, and the Kayin. Notwithstanding traditional avoidance of political activity, monks often participated in politics and the independence struggle.

Since 1948 when the country received independence from Great Britain, both civil and military governments have supported Theravada Buddhism. The 1947 Constitution states, “The State recognizes the special position of Buddhism as the faith professed by the great majority of the citizens of the Union.” The Ministry of Religious Affairs, created in 1948, was responsible for continuing Buddhism in Myanmar. In 1954, the Prime Minister, U Nu, convened the Sixth Buddhist Synod in Rangoon (Yangon), which was attended by 2,500 monks. It was during this time that the World Buddhist University was established.

During the military rule of Ne Win (1962-1988), he attempted to reform Burma under the Burmese Way to Socialism which contained elements of Buddhism.

Myanmar retains Buddhism traditions, some of which are quite unique. After a child passes 7-year age, the parents send him to the monastery to practice Buddhist teachings and receive education. Before children leave, they celebrate by a ceremony called “Shinbyu”. Boys dress like princes and ride the horse as Buddhists. That was the way the Buddha left his royal family to search the truth. Myanmar people believe that doing so would help boys achieve better adulthood.

Buddhism contributes to Burmese politics. Burmese nationalism first began with the Young Men’s Buddhist Associations (YMBA) - modeled after the YMCA - which started to appear all over the country. Civilian governments patronized Buddhism after independence. Leaders of political parties and parliamentarians, in particular U Nu, passed Buddhist influenced legislations, and declared Buddhism the state religion.

In Myanmar today there are over 400,000 monks and 75,000 nuns, 6,000 viharas and countless pagodas. About 1,000 of the viharas serve as educational institutions for the monastic community. Some of the larger monasteries have over 1000 monks studying the Buddhist scriptures and meditation practices.

It is interesting that nuns in Myanmar have a much higher status than in some other Eastern countries. Myanmar has the largest number of nuns in the world. They are well respected by their own people and usually have their own independent monastic and meditation centers. Many nuns have an equal or greater level of spiritual and scholarly attainment as the monks.

One monastery in Mandalay has 2,600 monks devoted to the study of the Pali Canon, The Commentaries and Sub-Commentaries. Monastic institutions of this type and size are unique in the world today and exist only in Myanmar. There are also several meditation centers for lay people and monastics, each catering for over 1,000 meditators. The ordinary people of Myanmar are very much involved in supporting all this.

In 1998, The Buddhist University was established. It is a permanent center of higher learning of Theravada Buddhism, located on the beautiful site of the sacred Dhammapala hill near the Sacred Tooth Relic Pagoda, Yangon.

Myanmar’s history of Buddhism is portrayed by a landscape filled with pagodas which is why the country is often called “the land of pagodas.” The Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon is surrounded by myths, and represents faith of the people who have worshipped there for generations. Shwedagon Pagoda has been a local venue for large meetings where both Aung San and his daughter Aung San Suu Kyi had made their famous speeches. The second university strike in history of 1936 was also held at that location. Every village in Myanmar has a pagoda, which is the place for worship and education.

Due to its many ancient pagodas, UNESCO has long tried to designate Bagan (formerly Pagan) as World Heritage Site, but unfortunately failed.

Thailand

Thailand

As the state religion, Buddhism in Thailand is largely of the Theravada school. As much as 94% of Thailand’s population is Buddhist of the Theravada school, though Buddhism in this country has become integrated with folk beliefs such as ancestor worship as well as Chinese religions from the large Thai-Chinese population. Owing to the tremendous influence Buddhism exerts on the lives of its people, Thailand is called by many foreigners “The Land of Yellow Robes,” for yellow robes are the garments of Buddhist monks.

There is no uniform opinion concerning when Buddhism was propagated into Thailand. It is widely believed by Thais, that Indian Emperor Ashoka sent Buddhist missionaries to Thailand in the 3rd century BC. Mahavamsa, the ancient Ceylon chronicle, described the Ashoka missionary groups to nine territories. Among them, two Theras (elder monks), Sona and Uttara, were sent to Suvarnabhumi. Scholars from different countries argue about its exact location, though some thought it was in Thailand. Others hold the view that Thailand received Buddhism much later. Various archeological remains unearthed at Nakon Pathom, however, indicate that perhaps Buddhism was introduced into Thailand as early as the 3rd century BC.In history, Indian traders and settlers did for seven hundred years frequent the shores of Thailand. The early settlers brought both Hinduism and Buddhism, as evidenced by numerous images of Vishnu, Shiva and Buddha found in early sites in Thailand. Animism antedated both Hinduism and Buddhism in Thailand and has persisted to the present day, chiefly in the form of spirit shrines at doors, yards and business premises. By the 6th century AD, Buddhism had already been well established in south and central areas of what is now Thailand. Later, Mahayana and Tantra together with Hinduism became the predominant religions.

The first form of Buddhism in Thailand was Theravada imported from Sri Lanka, which also had the most visible influence. While there are significant local and regional variations, the Theravada school provides most of the major themes of Thai Buddhism. By tradition, Pāli is the language of religion in Thailand. Scriptures are recorded in Pāli, using either the modern Thai script or the older Khom and Tham scripts. Pāli is also used in religious liturgy, despite the fact that most Thais understand very little of this ancient language. The Pāli Tipitaka is the primary religious text of Thailand, though many local texts have been composed in order to summarize the vast number of teachings found in the Tipitaka. The monastic code (Patimokkha) followed by Thai monks is taken from the Pāli Theravada- something that has provided a point of controversy during recent attempts to resurrect the bhikkuni lineage in Thailand.

The Monks of southern Burma adopted Theravada Buddhism at an early date and thereafter influenced the religious history of Thailand by invading the central valley of the Menam Chao Phya and setting up the Kingdom of Dvaravati which lasted from the 3rd to the 7th centuries. They left numerous stupas and a distinctive style of Buddhist image. Theravada Buddhism in Thailand was further strengthened after King Anawrahta of Burma captured Thanton in 1057. From there he carried to his capital at Pagan a number of Theravadin monks together with the Pali canon, and being an ardent Theravadin, he spread his religion along with his conquests in northern Thailand. Later as the Thai moved south from Yuman in the 12th and 13th centuries they came in contact with this form of Buddhism. When they set up the Thai Kingdom of Sukhothai in about 1238, Theravada Buddhism became the state religion.

With the growth of Mahayana Buddhism in India, the sect also spread to the neighboring countries. It is probable that Mahayana Buddhism was introduced to Burma, Pegu (Lower Burma) and Dvaravati (now Nakon Pathom in Western Thailand) from Magadha (in Bihar, India) at the same time as it went to the Malay Archipelago. But probably it did not have any stronghold there at that time; hence no spectacular trace was left of it. By about 757 AD (Buddhist Era: 1300), the Mahayanists Srivijaya king rose in power and spread his empire throughout the Malay Peninsula and Archipelago. Part of South Thailand (from Surasthani downwards) came under its rule. Srivijaya encouraged and supported propagation of Mahayana. In South Thailand today there is much evidence of Mahayana prevalent there. Nevertheless, there are no indications that the Mahayana superseded the Theravada in any way. This was due to the fact that Theravada Buddhism was already on a firm basis in Thailand when Mahayana was introduced there.

Besides Buddhism itself, Hindu beliefs received from Cambodia also had quite influence on Thai Buddhism, particularly during the Sukhothai period. Vedic Hinduism played a strong rule in the early Thai institution of kingship, just as it did in Cambodia, and exerted influence in the creation of laws and order for Thai society as well as Thai religion. Certain rituals practiced in modern Thailand, either by monks or by Hindu ritual specialists, are either explicitly identified as Hindu in origin, or are easily seen to be derived from Hindu practices. While the visibility of Hinduism in Thai society has diminished substantially during the Chakri dynasty, Hindu influences - particularly shrines to the god Brahma- continue to be seen in and around Buddhist institutions and ceremonies. Sanskrit, the sacred language of the Hindus, took its root deep in Thailand during these times.

In modern times, additional Mahayana influence has stemmed from the presence of Chinese immigrants in Thai society. While some Chinese have “converted” to Thai-style Theravada Buddhism, many others maintain their own separate temples in the East Asian Mahayana tradition. The growing popularity of the goddess Kuan Yin in Thailand (a form of Avalokitesvara) may be attributable to the Chinese Mahayanist presence in Thailand.

Some aspects of folk religion such as attempts to propitiate and attract the favor of local spirits known as phi form another major influence on Thai Buddhism. While Western observers (as well as urbane and Western educated Thais) have often drawn a clear line between Thai Buddhism and folk religious practices, this distinction is rarely observed in more rural locales. Spiritual power derived from the observance of Buddhist precepts and rituals is employed in attempting to appease local nature spirits. Many restrictions observed by rural Buddhist monks are derived not from the orthodox Vinaya, but from taboos derived from the practice of folk magic. Astrology, numerology, and the creation of talismans and charms also play a prominent role in Buddhism as practiced by the average Thai- topics that are, if not proscribed, at least marginalized in Buddhist texts. Additionally, more minor influences can be observed stemming from contact with Mahayana Buddhism. Early Buddhism in Thailand is thought to have been derived from an unknown Mahayana tradition. While Mahayana Buddhism was gradually eclipsed in Thailand, certain features of Thai Buddhism- such as the appearance of the bodhisattva Lokesvara in some Thai religious architecture, and the belief that the king of Thailand is a bodhisattva himself- reveal the influence of Mahayana concepts. The only other bodhisattva prominent in Thai religion is Maitreya; Thais sometimes pray to be reborn during the time of Maitreya, or dedicate merit from worship activities to that end.

The history of Thailand begins in the 13th century with the rise of the Sukhothai Kingdom, whose people were one in blood and language with the present Thais. Under devout kings of Ayudhya, Buddhism flourished, and by 1750 must have accumulated great quantities of sacred writings and valuable chronicles connected with the Monastic Order. Practically all such writings were destroyed in the devastation that attended the Burmese invasion of 1766-1767. Ayudhaya, the capital, fell after a siege of fourteen months during which fires and epidemics ravaged the city. However, by the 13th and 14th centuries monks from Sri Lanka succeeded in establishing Theravada Buddhism and it has remained the state religion ever since.

The first two kings of the present Chakri dynasty, who reigned from 1782 to 1824, are known by the names of Phra Buddha Yod Fa and Phra Buddha Loet la. While the third king, Phra Nang Klao, did not possess the name “Buddha”, he was known for his devotion to the Order and his aid in temple building and scriptural revision. The son of King Mongkut, Prince Vajirayanvaroros was virtually head of the Buddhist Monastic Order from 1892 to 1910; until his death in 1921 he was Prince Patriarch. Thereafter a grandson of Rama III became Prince Patriarch and filled this high position until his death in 1937. It has been the custom of all the Thai kings to serve a novitiate in the temple of their youth, thus the Throne has been closely bound to the Buddhist Order by ties of experience as well as by personal interest.

Thailand is perhaps the only country in the world where the king is constitutionally stipulated to be a Buddhist and the upholder of the Faith. In the 19th century King Mongkut, himself a former monk, conducted a campaign to reform and modernize the monkhood, a movement that has continued in the present century under the inspiration of several great ascetic monks from the northeast of the country.

Formerly, and in accordance with the Administration of the Bhikku Sangha Act (1943), the Sangha organization in Thailand was on a line similar to that of the State. The Sangharaja or the Supreme Patriarch is the highest Buddhist dignitary, whose is chosen by the King in consultation with the Government from among the most senior and qualified members of the Sangha. The Sangharaja appoints a council of Ecclesiastical Ministers headed by the Sangha Nayaka, whose position is analogous to that of the Prime Minister of the State. Under the Sangha Nayaka there function four ecclesiastical boards, namely the Board of Ecclesiastical Administration, the Board of Education, the Board of Propagation and the Board of Public Works.

Each of the boards has a Sangha Mantri (equivalent to a minister in the secular administration) with his assistants. The four boards or ministries are supposed to look after the affairs of the entire Sangha. It may be pointed out here that all religious appointments in Thailand are based on scholarly achievements, seniority, personal conduct and popularity, and contacts with monks further up in the Sangha.

There is a Department of Religious Affairs in the Ministry of Education which acts as a liaison office between the Government and the Sangha. All temples and monasteries are State property.

There are two Buddhist sects or Nikayas in Thailand. One is Mahanikaya, and the other is Dhammayuttika. Mahanikaya is older and by far the more numerous one, with the ratio of the two sects being 35 to 1. Dhammayuttika Nikaya was founded in 1833 by King Mongkut. The differences between the two Nikayas are not great; at most they concern only matters of discipline, and never of the Doctrine. Monks of both sects follow the same 227 Vinaya rules as laid down in the Patimokkha of the Vinaya Pitaka (the Basket of the Discipline), and both receive the same esteem from the public. In general appearance and daily routine of life, except for the slight difference in the manners of putting on the yellow robes, monks of the two Nikayas differ very little from each other.

Unlike Burma and Sri Lanka, the female Theravada bhikkuni lineage was never established in Thailand. Lay women primarily participate in religious life either as lay participants in collective merit-making rituals, or by doing domestic work around temples. A small number of women choose to become Mae Ji, non-ordained religious specialists who permanently observe either the eight or ten precepts.

Young men typically do not live as a novice more than one or two years. At 20, they become eligible to receive upasampada, the higher ordination to establish them as a full bhikku. Temporary ordination is the norm among Thai Buddhists. Most young men traditionally ordain for the term of a single rainy season (known in Pāli as vassa, and in Thai as phansa). Those who remain monks beyond their first vassa typically remain monks for between one and three years. After this period, most young monks return to lay life for marriage and family. A period as a monk is a prerequisite for many positions of leadership within the village hierarchy. Most village elders or headmen were once monks, as were most traditional doctors, spirit priests, and some astrologists and fortune tellers.

There are about 21,000 wats in Thailand. In Bangkok alone there are nearly two hundred, and some have as many as 600 resident monks and novices. Wats are centers of Thai art and architecture, also the most important institution in rural life. The social life of rural communities revolves around the wat. Besides routine religious activities, a wat serves the community as a recreation center, dispensary, school, community center, home for the aged and destitute, social work and welfare agency, village clock, rest-house, news agency, and information center.

From the 1st to 7th centuries, Buddhist art in Thailand was first influenced by direct contact with Indian traders and the expansion of the Mon kingdom, leading to the creation of Hindu and Buddhist art inspired from the Gupta tradition, with numerous monumental statues of great virtuosity.

From the 9th century, the various schools of Thai art then became strongly influenced by Cambodian Khmer art in the north and Sri Vijaya art in the south, both of which are Mahayana faith. Up to the end of that period, Buddhist art had been characterized by a clear fluidness in the expression, and the subject matter is characteristic of the Mahayana pantheon with multiple creations of Bodhisattvas.

From the 13th century, Theravada Buddhism was introduced from Sri Lanka around the same time as the ethnic Thai kingdom of Sukhothai was established. The new faith inspired highly stylized images in Thai Buddhism, with sometimes very geometrical and almost abstract figures.

During the Ayutthaya period (14th -18th centuries), the Buddha came to be represented in a more stylistic manner with sumptuous garments and jeweled ornamentations. Many Thai sculptures or temples tended to be gilded, and on occasion enriched with inlays.

Buddhist temples in Thailand are characterized by tall golden stupas, and the Buddhist architecture of Thailand is similar to that in other Southeast Asian countries, particularly Cambodia and Laos, with which Thailand shares cultural and historical heritage.

Laos

Laos

Buddhism practiced in Laos is Theravada, using Pali language. Landlocked and surrounded by more powerful cultures, Laos remains the poorest country in Southeast Asia nearly in every way.

The faith of Buddhism was introduced beginning in the 8th century by Mon Buddhist monks and has been widespread by the 14th century. A number of Laotian kings were important patrons of Buddhism. Virtually all lowland Lao were Buddhists in the early 1990s, as well as some Lao Theung who have assimilated to lowland culture. Since 1975 the communist government has not opposed Buddhism but rather has attempted to facilitate its political goals. In the early 1990s, increased prosperity and relaxation of political control stimulated the revival of popular Buddhist practices.Besides almost universal acceptance of Buddhism, most Laotians also believe in the rich traditional spiritual life, Animism. The belief in phi (spirits) affects the people’s relationship to nature, provides a cause of illness and misfortune, and shapes interpersonal relationships. Phi has much in common with the spirits of the land worshipped in other Southeast Asian countries. Many of the Wats have small spirit huts included on their grounds and many of the village monks are respected as having the ability to exorcise malevolent spirits or contact favorable ones.

The original inhabitants of Laos were Austro-Asiatic peoples living by hunting and gathering before the advent of agriculture. The Mekong became the most important river as its many tributaries allowed traders to penetrate deep into the hinterland, where they bought products such as cardamom, gum benzoin, and foods. With development of agriculture and fiefdoms, a plurality of power centers occupied the middle Mekong Valley in early times. At its peak, Funan, had its mandala incorporate parts of central Laos.

Lao history in fact begins in the 14th century with a risqué event, the seduction of one of the king’s wives by his son Phi Fa, who and whose son Fa Ngum journeying south later stayed in Khmer royal court at Angkor. There, Fa Ngum studied under a Theravadin monk, gained favor of the Khmer king, and eventually married one of his daughters. In about 1350, the king of Angkor helped Fa Ngum to reassert control over his father’s lost inheritance.

By this time, Angkor was in a state of decline, and the power center in Thailand had shifted southward from Sukkhothai to Ayutthaya. Those helped Fa Ngum to establish an independent kingdom, with ties to Angkor, along the upper reaches of the Mekong River. Fa Ngum’s coronation at Luang Phrabang in 1353 marked the beginning of the historical Laos state. It also established the farthest northern extent of Khmer civilization, since Fa Ngum’s kingdom was modeled on Angkoran precedents even though the Laos are racially related to the Thais. Moreover, Fa Ngum invited his Buddhist teacher at the Khmer court to act as his advisor and chief priest. Under his influence the new kingdom of Laos became firmly Theravadin, as it has remained to the present day. This Buddhist master brought with him from Angkor a Buddha image known as the “Phra Bang”. This image accounts for the capital’s name and like the tooth relic of the Buddha in Sri Lanka, became the palladium of the kingdom.

From beginning, Laos seems to be just strong enough to maintain a separate identity in the midst of its more powerful neighbors. Because of the relatively weak central government of Laos, Theravada Buddhism became the primary instrument to hold together ethnic groups and inaccessible villages scattered through the mountains. According to the Lao model of kingship, the king on throne is not much because of divine right as because of his obviously good karma in previous lives. He was expected to continue that good karma in this life by supporting the Sangha and promoting Buddhism through royal construction projects. Pursuing this role, King Visun (1501-1520) is remembered as the prime mover behind the splendor of Luang Phrabang, the first capital of Laos. Visun brought to fruition an ambitious Buddhist construction program begun by his two older brothers in order to repair damage by the Vietnamese. Luang Phrabang remains the site of some of the most attractive Buddhist monuments and ruins in Southeast Asia.

Visun’s grandson Setthathirat occupied the throne in 1548, shifted the capital from Luang Phrabang to Vien Chan, a site closer to the Thai capital at Ayutthaya and more conducive to trade with and supervision by the Thais.

Remnants of Sutthathriat’s works still stand, the most notable being the hundred-yard square That Luang or “Great Shrine”, a temple mountain built in the Khmer style. Setthathriat also built a second grand temple to house a precious jade Buddha known as the Phra Keo. This image was the second palladium of Laos until it was removed to Bangkok by a Thai invading force in 1778. It has remained in Bangkok ever since in the Wat Phra Keo as Thailand’s most sacred image.

In 1782, the Thais restored the Vietnamese dynasty as a puppet regime in Vien Chan and returned the Phra Bang Buddha image. Despite continuing Thai domination of the entirety of Laos, the country remained divided into a northern and southern kingdom until 1893, when the French blockaded Bangkok and forced Thailand to cede to France the upper reaches of the Mekong River. The French protectorate thus established over Laos had little to do with the distribution of the Lao people, many of whom still resided in Thai territory.

After World War II, The French collapse in Southeast Asia in 1954 led to a coalition government in which both Lao royalists and Lao communists were represented. This coalition quickly collapsed, and Laos, like Vietnam, entered the 1960’s in the throes of a full-scale civil war between communist and pro-Western factions. After the American defeat in Vietnam in 1975, the communists quickly gained control.

Beginning in the late 1950s, the Pathet Lao attempted to convert monks to the leftist cause and to use the Sangha’s influence to increase their status among the people. The politicization of the monastic community continued after the assumption of power by the Pathet Lao in 1975. As mild attitude the government holds toward Buddhism, many monks compelled to spread party propaganda fled to Thailand, while other pro-Pathet Lao monks joined the newly formed Lao United Buddhists Association, which replaced the former religious hierarchy. The number of men and boys ordained dropped and many Wats were emptied. 1979 saw the lowest point of Buddhism in Laos.

From the late 1980s, stimulated by economic reform and political relaxation, donations to wat and participation in Buddhist festivals increased. Festivals at villages and neighborhood level became more elaborate, ordinations increased, and household blessing ceremonies conducted by monks began to recur. Buddhism in Laos has been changed by the socialist government, however, its importance to lowland Lao and the organization of Lao Loum society remained fundamental.

In Laos, all males generally spend a period of time as a monk in youth, from one week to as long as several years, but typically 2-4 months. Ordination to a monk brings great merit to the boy as well as his parents. It had the advantage in that the novices were taught to read and write as well as learning about Buddhist precepts. This time in the monastery generally during the rainy season is often called the “retreat”, between the months of June and October. Young monks observe 75 rules and full-fledged monks vow to observe the 227 rules of monastic order.

Like other Southeast Asian countries, Buddhism in Laos brings people festivals in the agricultural working year. The first, Bun Pha Wat, occurs in January, at different dates in different villages, and commemorates the life story of Buddha in one of his previous incarnations. The Magha Puga ceremony, held on the full moon night in February, commemorates the first sermon of Buddha in the Deer Park. The festival consists of parades of worshippers bearing candles circling local temples, music and chanting. In March, a harvest festival, Boun Khoun Khao is celebrated in which the villagers give gifts to the monastery. One of the most important celebrations occurs in April and last several days. Boun Pimai, the Lao New Year, is characterized by, among other things, the throwing of buckets of water on all people. Symbolizing the washing away of sins and a new beginning, the festival also involves washing Buddha statues, feasts, visiting family and temples, dancing and singing.

The Visakha Puja, memory of the Buddha’s birth, enlightenment and death, occurring in May, is celebrated by candlelit processions to temples and sermons. The rocket Festival (Boun Bang Fai) at the same time is a remnant of pre-Buddhist rain-making ceremonies, highlighted by the firing of huge, ornate, homemade bamboo rockets. Rocket makers are honored if their rockets fly the highest.

The most sacred time in the Buddhist calendar is the Rain Retreats, also the Buddhist Lent in English. Lay people undertake fasts or meditations, and imitate the lives of monks and nuns. Usually no wedding is held during the Retreats. It begins and ends with celebrations: the Khao Phansaa on the first full moon in July and the Awk Phansaa on the first full moon in October.

In August, the Haw Khao Padap Din festival occurs. This is a day devoted to remembering and paying respect to the dead. While this festival is observed through the Buddhist world, one unusual aspect of the Laotian ceremony is that recently dead bodies are exhumed, cleaned and cremated, to the prayers and chanting of monks and nuns.

The focal point of every village and town is the temple or the Wat. This is a symbol for village identity, the focus of the festivals, the site of local schools, and the residence of the monks. Depending on the wealth and contributions of the villagers, the buildings vary from simple wood and bamboo structures to large, ornate brick and concrete edifices decorated with colorful murals and tile roofs shaped to mimic the curve of the naga, the mythical snake or water dragon. An administrative committee made up of respected older men manages the financial and organizational affairs of the Wat.

The Pha That Luang, Wat Sisakhet, Wat Xieng Thong, and That Dam are all Buddhist structures in Laos. Lao Buddhism is also famous for images of the Buddha performing uniquely Lao mudras, or gestures, such as calling for rain, and striking uniquely Lao poses.

Lao artisans have, throughout the past, used a variety of mediums in sculpture. Bronze is probably the most common, gold and silver images also exist. The Phra Say of the sixteenth century is made of gold, carried home by Siamese as booty in the late 18th century. Today, it is in enshrined at Wat Po Chai in Nongkhai, Thailand. The Phra Say’s two companion images, the Phra Seum and Phra Souk, are also in Thailand. Perhaps the most famous sculpture in Laos is the Phra Bang, also cast in gold, but the craftsmanship is held to be of Sinhalese rather than Lao origin. Tradition maintains that relics of the Buddha are contained in the image.

A number of colossal images in bronze exist. Most notable of these are the Phra Ong Teu (16th century) of Vientiane, the Phra Ong Teu of Sam Neua, the image at Vat Chantabouri (16th century) in Vientiane and the image at Wat Manorom (14th century) in Luang Phrabang, which seems to be the oldest of the colossal sculptures. The Manorom Buddha, of which only the head and torso remain, shows that colossal bronzes were cast in parts and assembled in place.

The most famous two sculptures carved in semi-precious stone are the Phra Keo (The Emerald Buddha) and the Phra Phuttha Butsavarat. The Phra Keo, which is probably of Xieng Sen (Chiang Saen) origin, is carved from a solid block of jade. It had rested in Vientiane for two hundred years before the Siamese carried it away as booty in the late 18th century. Today it serves as the palladium of the Kingdom of Thailand, and resides with the king at the Grand Palace in Bangkok. The Phra Phuttha Butsavarat, like the Phra Keo, is also enshrined in its own chapel at the Grand Palace in Bangkok. Before the Siamese seized it in the early 19th century, this crystal image was the palladium of the Lao kingdom of Champassack.

In the Pra Lak Pra Lam, the Lao Ramayana, instead of having Rama portrayed as an incarnation of Vishnu, Rama is an incarnation of the Buddha. Lao people have also written many versions of the Jataka Tales.

Cambodia

Cambodia

Buddhism in Cambodia dates back to at least the 5th century AD. Jayavarman of Fu-nan, Suryvarman I and Jayavarman VII were all Buddhists. Up to the 13th century, Cambodia was primarily influenced by Mahayana Buddhism and Saivism. After the 13th century Theravada Buddhism became the main religion of Cambodia, and today ninety-five percent of Cambodians hold Theravada, the country’s official religion.

The beginning of Buddhism in the present-day area of Cambodia might be traced back to more than two thousand years ago. In 238 BC Emperor Ashoka sent two Bhikkus named Sona Thera and Utara Thera to propagate Buddhism in Suwanaphumi, Southeast Asia today. From that time Buddhism has flourished throughout the land of Suwanaphumi, and some main events can be noted in various ancient kingdoms, especially Funan Kingdom (first state of present-day Cambodia).Among the kings of Funan dynasty, Kaundinya Jayavarman (478-514 AD) sent a mission to China under the leadership of a Buddhist monk named Nagasena from India. During the reign of the same Chinese emperor, two learned Khmer monks Sanghapala Thera and Mantra Thera of Funan went to China in the early years of the 6th century AD to teach Buddhism and meditation for the emperor of China. Bhikku Sanghapala had translated an important Buddhist scripture Vimutti Magga (the Way of Freedom) which they believed was older than Visutthi Magga (the Way of Purity) of Buddhagosacara. Now this scripture has only Chinese version in existence and many Buddhist countries have translated it into their own language.

King Rudravarman (514-539 AD) is said to have claimed that in his country there was a long Hair Relic of Lord Buddha for his people to worship. Tharavada preached in Sanskrit language flourished in Funan in the 5th century and the early years of the 6th century. Around the 7th century, the popular usage of Pali language in the southern region suggested the strong appearance of Theravada Buddhism in Cambodia.

The great emperor, Yasovarman (889-900 AD) established a Saugatasrama and elaborated regulations for the guidance of this asrama or hermitage when Buddhism and Brahmanism(both Visnuism and Vaisnavism) flourished in Cambodia. During the reign of Jayavarman V (968-1001 AD), the successor of Rajendravarman II, Mahayana Buddhism grew with increasing importance. The king supported Buddhist practices and invoked the three forms of existence of the Buddha. In this way, up to the 10th century AD, Mahayana Buddhism had become quite prominent.

Pramakramabahu I, the king of Sri Lanka, is said to have sent a princess as a bride probably for Jayavarman VII, son of Dharnindravarman II (1150-1160 AD), who was the crown prince. King Jayavarman VII (1181-1220 AD) was a devout Buddhist and received posthumously the title of Mahaparamasaugata. The king patronized Mahayana Buddhism and historical records about him express beautifully the typical Buddhist view of life, particularly the feelings of charity and compassion towards the whole universe. His Taprohm Inscription informs us that there were 798 temples and 102 hospitals in the whole kingdom, and all of them were given full support by the king. One of the monks who returned to Burma with Capata Bhikku was Tamalinda Mahathera, who most probably was the son of the Cambodian King Jayavarman VII. Under the threat of flowing of Sihala Buddhism, his prestige diminished, his temporal power crumbled away, and the god-king worshipping was concealed. Theravada Buddhism had become the predominant religion of the people of Angkor by the end of Jayavarman VII ‘s reign.

In the second half of the 12th century, Sri Lanka’s fame as the fountain-head of Theravada Buddhism reached the Buddhist countries of Southeast Asia. The knowledge of Sinhala Buddhism was so widespread and the Sinhala monks were so well-known to the contemporary Buddhist world. At this time a Cambodian prince is said to have visited Sri Lanka to study Sinhala Buddhism under the guidance of the Sinhala Mahatheras. Buddhism continued to flourish in Kambuja in the 13th century but yet to become the dominant religious sect in the country. After then, Theravada became the main type of Buddhism in Cambodia. The change was undoubtedly due to the influence of the Thais, who were ardent Buddhists and had conquered a large part of Cambodia land. Under the influence of the Thais, Sinhala Buddhism was also introduced to Cambodia. With the passage of time, the Brahmanical Gods like those worshipped during the Angkor period were replaced by Buddhist images. Gradually, Buddhism became the dominant creed in Kambuja and today there is hardly any trace of the Brahmanical religion in the country.

The Jinakalamali gives an account of the cultural connection between Cambodia and Sri Lanka in the 15th century. It states that 1967 years after the Mahaparanibbana of Lord Buddha, eight monks headed by Mahananasiddhi from Cambodia with 25 monks from Nabbispura in Thailand came to Sri Lanka to receive the Upasampada ordination at the hands of the Sihalese Mahatheras. Buddhism continued to flourish in Cambodia in the 16th century . King Ang Chan (1516-1566), a relative of king Dhammaraja, was a devout Buddhist. He built pagodas in his capital and many Buddhist shrines in different parts of Cambodia. In order to popularize Buddhism, King Satha (1576-1594), son and successor of Barom Reachea, restored the great third floor of Angkor Wat (in the past it was erected and dedicated to the God of Visnu), which was built by King Suriyavarman II (1130-1150), which had become a Buddhist shrine or Buddhist temple by the 16th century. During the 17th and 18th centuries, Thailand’s interference in Cambodia’s politics helped the former to influence the religious world of the latter. Though Thailand disturbed Cambodia’s politics and hampered its progress but the Thai kings and their Buddhist world made contribution to the progress of Buddhism in Cambodia.

After gaining liberation from French colonists, Cambodia Buddhism grew up again under the patronage of King Norodom Sihanouk. In that time Cambodia had many Buddhist scholars such as Somdech Choun Nat, Somdech Hout Tat, Pang Khat and Kiev Chom, etc, as the active leaders of developing Buddhism in Cambodia. During the reign of Sihanouk, Buddhism was made state religion of Cambodia.

In 1975, communists took control of Cambodia and try to destroy Buddhism. Religious practices were forbidden, and temples, pagodas, and Buddhist libraries systematically destroyed. In 1981, about 4,930 monks served in 740 wats in Cambodia. The Buddhist General Assembly reported 7,000 monks in 1,821 active wats a year later. In 1969 by contrast, observers estimated that 53,400 monks and 40,000 novice monks served in more than 3,000 wats. It is estimated that about 50,000 monks lost their lives during the Khmer Rouge regime.

Buddhism plays substantial functions in Cambodia. Besides the traditional role of monks in participation in all formal village festivals, ceremonies, marriages, and funerals, Buddhism also plays its part in politics, especially in education. Until the 1970s, most literate Cambodian males had gained literacy solely through the instruction of the sangha. Today Buddhism is struggling to re-establish itself although the lack of Buddhist scholars and learned leaders and the continuing political instability are making the task difficult. The Preah Sihanouk Raja Buddhist University has been established and the state manages to develop Pali schools and the 1931 royally-founded Buddhist institutes.

Two monastic orders constitute the Buddhist clergy in Cambodia. The larger group, to which more than 90 percent of the clergy belonged, was the Mohanikay. The far smaller order, Thommayut, was introduced into the ruling circles of Cambodia from Thailand in 1864, and has revived in recent years; it gained prestige because of its adoption by royalty and by the aristocracy, but its adherents were confined geographically to the Phnom Penh area. Among the few differences between the two orders is stricter observance by the Thommayut bonzes (monks) of the rules governing the clergy. In 1961 the Mohanikay had more than 52,000 ordained monks in some 2,700 wats, whereas the Thommayut order had 1,460 monks in just over 100 wats. In 1967 more than 2,800 Mohanikay wats and 320 Thommayut wats were in existence in Cambodia. Each order has its own superior and is organized into a hierarchy of eleven levels. The seven lower levels are known collectively as the thananukram; the four higher levels together are called the rajagana. Each monk must serve for at least twenty years to be named to these highest levels.

History left Cambodia and Buddhism great legacy, the Angkor sites. Angkor Thom, the great city, was the last and enduring capital of Khmer Empire from the 9th to 15th century. In mid 15th century, the Siamese captured and sacked the city. Temples were destroyed and inhabitants driven to south. Angkor city was abandoned and left to ruins some time prior to 1609. The city lies at the right bank of Siem Reap river, nearly 2km north to the gate of Angkor Wat. Angkor Thom is in the Bayon style. This manifests itself in the large scale of the construction, in the widespread use of laterite, in the face-towers at each of the entrances to the city and in the naga-carrying giant figures which accompany each of the towers.

Among the temples, Angkor Wat is the peak. It is a temple complex in northwest Cambodia, the world’s largest religious structure, about 1550 meters by 1400 meters. Angkor Wat was built in the early 12th century by King Suryarman II to protect his kingdom and people, and to worship gods. Angkor Wat was initially dedicated to Vishnu and then to Buddhism. The Wat, an artificial mountain originally surrounded by a vast external wall and moat, rises in three enclosures toward a flat summit. The five remaining towers (shrines) at the summit are composed of the repetitive diminishing tiers typical of Asian architecture, more Cambodian actually. There were about 600 temples at Angkor Wat as it was discovered.

There are also other noteworthy temples at the large Angkor sites area. Bayon Temple, the state temple of Jayarvaman VII in the late 13th century, is located at the center of Angkor Thom, famous for its gigantic head sculptures. Others are Srei Preah Ko Temple (879), Banteay Temple (967), Prasat Kravan Temple (921), Pre Rup Temple (961), East Mebon Temple (953), and Banteay Kdei Temple, etc.

Down south in Phnom Penh, there are several famous Buddhist sites and architectures. The Silver Pagoda, built at the end of the 19th century, is a colonial-era masterpiece of native Khmer style, adjacent to the Royal Palace. Wat Phnom is the namesake and symbol of the capital city of Phnom Penh.

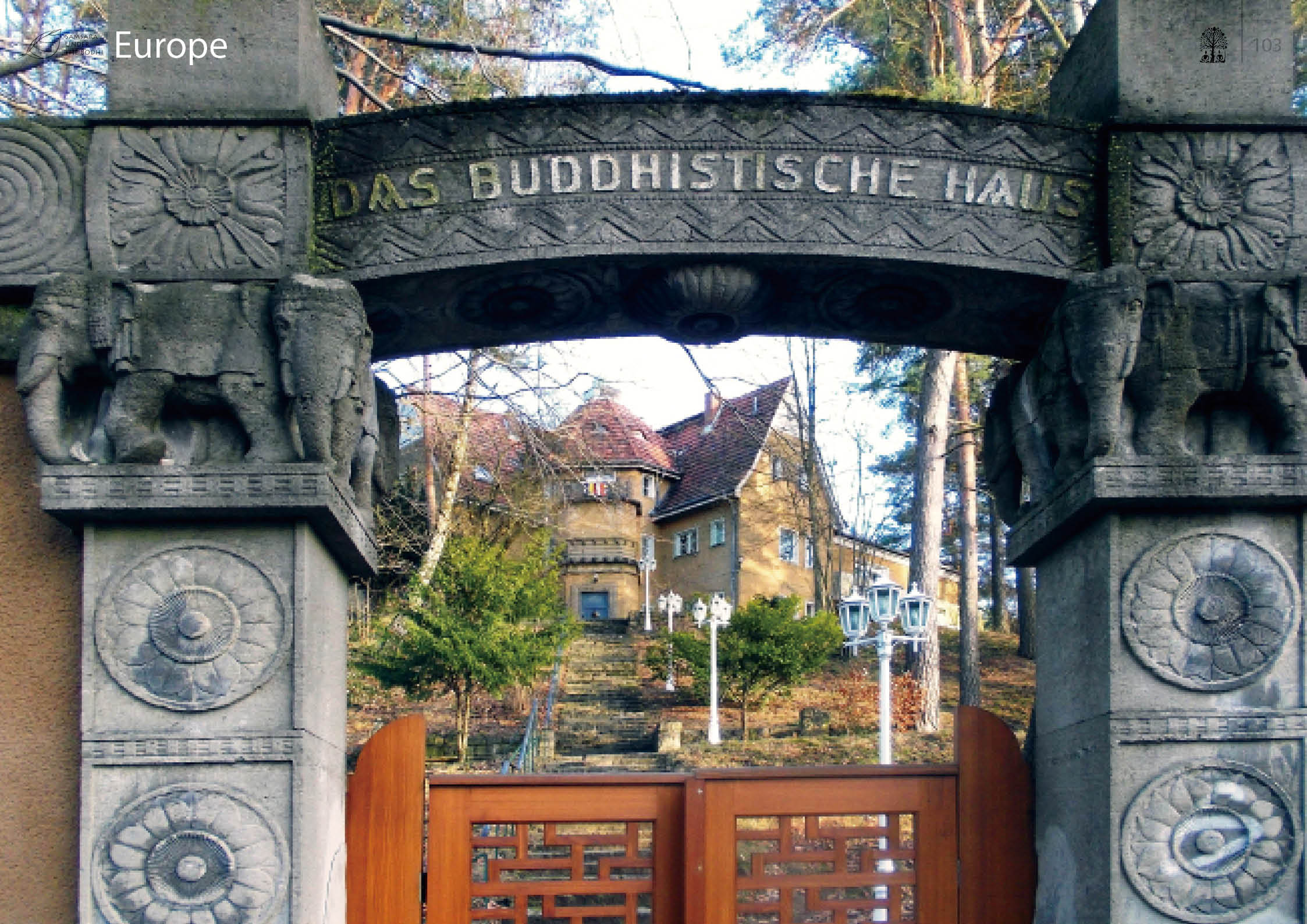

Europe

Europe

Although Buddhism spread throughout Asia, it had remained virtually unknown in the West until modern times. The early missions sent by the emperor Ashoka to the West did not bear fruit. European contact with Buddhism first began after Alexander the Great’s conquest of northwestern India in the 3rd century BC. Greek colonists in the region adopted Indian Buddhism and syncretized it with aspects of their own culture to make a sect called Greco-Buddhism which dominated the area of ancient India comprising modern day Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan for several centuries. Emperor Ashoka sent Buddhist missionaries to the Hellenistic world, where they established centers in places such as Alexandria, creating a noted presence in the region. Many prominent Hellenistic writers were well aware of Buddhist lore and tradition and wrote about it in detail. Some scholars believe that later Greek philosophers may have borrowed from the teachings of the Buddha and that Jesus Christ was influenced by certain principles.

Although the Buddha’s teachings have been known in countries throughout Asia for over 2,500 years, very few people in Europe or America would have known Buddhism before the 18th century. Buddhist attitudes of peace, mindfulness and care for all living creatures have come to be the concern of many groups in the West, so did the Buddhist attitude of “come and see for yourself”. In the eighteenth century onwards, a number of Buddhist texts were brought to Europe by people who had visited the colonies in the East. These texts aroused the interest of some European scholars who then began to study them. This may be called the discovery period of Buddhism in the West, during which the West was trying to find out and understand more about Buddhism.Although reports about Asian Buddhist beliefs and practices had been drifting back to Europe since the thirteenth century, a clear picture of Buddhism as a unitary whole did not take shape in Europe until the middle of the nineteenth century, just a little more than 150 years ago. Before then, the sundry reports that had reached scholars in Europe were generally haphazard, inaccurate, and conjectural, if not utterly fantastic. Around the middle of the nineteenth century, some Buddhist texts were translated into European languages.

The first person to comprehend Buddhism as a unitary tradition and establish its historical origins was the brilliant French philologist Eugene Burnouf. Burnouf had studied Pali, Sanskrit, and Tibetan manuscripts that had been sent to him in Paris from the East. Based on these texts, with barely no other clues, he wrote his 600-page tome, Introduction to the History of Indian Buddhism (1844), in which he traced in detail Indian Buddhist history and surveyed its doctrines and texts. Though later generations of scholars have greatly expanded upon Burnouf’s work and filled in many missing pieces, they regard as essentially accurate the outline of Indian Buddhism he proposed in his groundbreaking study.

Interests about Buddhism began circling among academic circles in modern Europe since the 1870s, with philosophers like Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche and esoteric-minded scholars such as Helena Blavatsky. By the early twentieth century, a large number of Buddhist texts had already been translated into English, French and German, including virtually the entire collection of Theravada scriptures as well as a number of important Mahayana texts.

During this period, Buddhist organizations were founded in the major cities of Europe. The oldest and one of the largest of these, the Buddhist Society of London, was established in 1924. These organizations helped the growth of interest in Buddhism through their meditation sessions, lectures and circulation of Buddhist literature.

The academic study of Buddhism initiated by these pioneers has continued through to the present time, despite the setback of two world wars and frequent shortages in funding. In Western universities and institutes, scholars map in ever finer details and with broader sweep the entire Buddhist heritage – from Sri Lanka to Mongolia, from Gandhara to Japan.

The transition in Western Buddhism was facilitated by two main factors. One was the increasing number of Asian Buddhist teachers who traveled to the West – Theravada bhikkus, Japanese Zen masters, Tibetan lamas – either to give lectures and conduct retreats, or to settle there permanently and establish Buddhist centers. The second factor was the return to the West of the young Westerners who had trained in Asia in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and now came back to their home countries to spread the Dharma.

Popularization of Buddhism in the West began roughly in the 1960s and continues through to the present. Buddhism comes to exert its appeal on an increasing number of people of different lifestyles and its following proliferates rapidly. At beginning Buddhism was largely a counter-cultural phenomenon, adopted by those in rebellion against the crass materialism and technocratic obsessions of modern society: hippies, acid heads, disaffected university students, artists, writers, and anarchists. But as these youthful rebels gradually became integrated into the mainstream, they brought their Buddhism with them.

Today Buddhism is espoused not only by those in the alternative culture, but by businessmen, physicists, computer programmers, housewives, real-estate agents, even by sports stars, movie actors, and rock musicians. Perhaps several hundred thousand Europeans have adopted Buddhism in one or another of its different forms, while many more quietly incorporate Buddhist practices into their daily lives. The presence of large Asian Buddhist communities in the West also enhances the visibility of the Dharma. Thousands of books on Buddhism are now available, dealing with the teachings at both scholarly and popular levels, while Buddhist magazines and journals expand their circulation each year. Buddhist influences subtly permeate various disciplines: philosophy and ecology, psychology and health care, the arts and literature, even Christian theology. Indeed, already three years ago Time magazine devoted a full-length cover story to the spread of Buddhism in America, and at least five books on the subject are in print.